I wrote a post some time ago on the design problem that seemed to be posing an unreasonable level of danger to cyclists - that of lorry cab designs.

red-lorry-yellow-lorry-dead-lorry

The point I was making that the cyclists are not to blame for the problem, even though safety campaigns are invariably aimed at them - a cut and dried case of the "victim blaming" typical in this kind of situation. I would go further and say that often the drivers of these vehicles are victims too, as they are put under extraordinary pressures as a direct consequence of the design of the vehicle they are often expected to manoeuvre quickly and safely through crowded urban streets.

If you applied basic health and safety thinking (of the kind that really has made a genuine difference to the way the construction industry operates in this country) to this problem, the design of the cabs themselves would be an obvious starting point for remedial action. It is sad that so many major construction companies are not extending their health and safety obligations resulting as a consequence of their operations beyond the gates of their site compounds, and insisting that lorries used in crowded urban areas are better designed.

I am therefore delighted to see that the London Cycling Campaign has come up with visuals that show exactly the kind of thing I had in mind, as reported in The Guardian:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2013/mar/19/cyclist-friendly-lorry-design-accidents

and as noted on the LCC website itself:

http://lcc.org.uk/pages/safer-lorries-safer-cycling

The biggest problem here for haulage companies and the extremely safety-aware major contractors that employ them is that these visuals look so entirely reasonable and sensible.

In a civilised world where people in cities come first, surely those in charge of governance would insist that the brutish and dangerous lorries were tamed before being allowed through the city gates? If you want to drive here, drive something safer.

Showing posts with label Urban Design. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Urban Design. Show all posts

19 March 2013

5 January 2012

The Need for Speed

We all love to hate the comments on the various blogs and comment sites where the enemy motorist thunders that cyclists who run red lights or ride on pavements effectively remove any moral right for those squeaky clean unoffending riders to complain about their lot. I love to get hot under the collar about that and I also particularly enjoy dutifully stopping at red lights and riding on stupidly dangerous roadways in a constant battle to reclaim the moral high ground. As Homer Simpson said "it's not marriage that's the problem, it's the constant battle for moral superiority that's the killer".

My latest bit of moral grandstanding involves my double life as a car driver. Yes dear reader, I do enjoy a dalliance with the dark side now and then, but then again don't we all...

I have decided to commit to drive as near as I can to the posted legal speed limits wherever I go in my car; that statement in itself saying something about what follows. As a result, I have discovered two highly connected things. Firstly, the vast majority of car drivers break the law with impunity and secondly, it is very difficult not to join in this mass protest action against authority. Actually, that makes it all sound a bit jolly and rebellious, whereas in reality of course it is a corrosive and antisocial disease that is killing our public spaces, but more on that later.

Now, this is not going to be an authoritative or scientifically accurate dissection of motor speeding rates. It is private blog written by a hobbyist after all. If you want facts, go to Wikipedia. All I know is that I am now the slowest and most cringingly annoying driver on the road. Wherever I go, other drivers behind me often get stressed and upset just because I am trying not to break the law. So really the ridiculousness of anyone using RLJs as evidence for why cyclists should be licensed, taxed, burned at the stake or whatever is quite overwhelming. These incentives obviously haven't worked for motorists. In fact the only main requirements of the highway code are that we drive on the left, don't smash into each other and don't drive too fast. We only really manage to drive on the left, despite all the taxes, licenses and bureaucracy that can be devised.

But, it is the second thing I discovered that interests me more than some boring and endlessly replayed argument about who stopped at the traffic lights and who didn't. The fact that breaking the speed limit is so easy should be the concern. I believe there is of course a cultural force at work here - my natural instinct to blend in and do as others do, to be part of the social "norm" makes it very difficult to drive differently (and thus slower) than everyone else, but It is also the case that antisocial speeding behaviour is all facilitated and condoned by the highway network itself. The engineering strategies that ensure large visibility splays, gentle radii to bends, easy gradients, shallow dips, open vistas and a smooth (!) well drained surface all in the name of safety have created the perfect risk-free environment to go faster and faster. It seems intellectually bizarre to create a system which facilitates certain behaviour, which you then try to prevent with unenforceable rules.

The "Twenty's Plenty" campaign on one hand stands as a recognition of the tragic fact that the risks of the game are not accurately relayed to the most dangerous protagonists, and on the other as the apogee of this whole daft approach. In a sensibly designed network, there would be no need for speed limits as it would be obvious what an appropriate speed was. The design itself would imply the right approach. This is a purely selfish notion - despite the warm glow of law abiding citizenry, I am sick of feeling like a twat driving at the legally correct 30mph over the Gabalfa flyover in Cardiff, designed in a similar style to the M4 just to the North, where 70mph is the limit. You could hit 100mph over that flyover without too much bother. Is it any wonder that so many fail this unfair morality test just a little every day?

I think it is fair therefore to consider the problem of speeding partly as an engineering failure, consistent with the failure to recognise that Dutch style road and cycle path design is the only sensible starting point if you wish to increase cycling rates. This is why the battles in London over key public spaces, such as Blackfriars, Kings Cross and Elephant & Castle are so important. It is at these locations that the clash of the arguments I have set out above has become clear and apparent. On one hand, we have the institutional engineering strategies of TfL that prioritise traffic flow over all else and which divorce the design from the appropriate behaviour. On the other, we have people demanding inherent safety and a genuine consideration of the importance of public realm, a sense of place and the way citizens use their public space.

The Cycling Embassy of Great Britain will play a crucial role here, as it seeks to open our eyes in the UK to the approaches and solutions used in other countries such as The Netherlands which have grappled with this same conundrum, but have typically come up with a far more grown up and civilised approach.

3 January 2012

More Dispatches from Spain

|

| Bike Parking in the centre of Palma de Mallorca |

We return from Spain again encouraged by the progress and openess we see there to alternative means of transport. Of course, they are still largely in thrall to the motor car (and moped), but there are definite green shoots in terms of a growing cycling culture. The beauty of a country like Spain is that whilst they remain very car orientated, people are very quick to adapt to and accept new ideas. They seem to have an in-built sense of civic duty that means that if something is suggested that will clearly have benefits for the civic realm then there seems to general acceptance, if not always complete support. This stands in contrast to the more overt conservatism in the UK, where new ideas are generally regarded with suspicion at best. I like to think that the focus on public space and quality urban realm that typifies a Spanish city like Palma de Mallorca comes from this belief in the idea of "civitas". Perhaps this is one of the cultural influences bequeathed to Spain by it's Moorish occupiers centuries ago.

|

| Typical docking station |

Either way, the green shoots are in evidence in Palma. In addition to the now a-typical bike hire scheme, carried out with the usual Spanish commitment and panache, there are also new cycling infrastructure interventions all over the city. They may be sub-standard when compared with best practice, such as the painted lanes that cross Plaza Espanya in a rather unlikely fashion, but there are also new two-way lanes with separating kerbs that have been borrowed from the carriageway and newly installed two-way lanes forming part of widened footways. The beginnings of what could become an extensive network are in place, mostly in the form of segregated routes - something that we can't sneer at at all in the UK, regardless of the criticisms that could be levelled at the two-way style and narrow widths.

What makes the difference is when the Spanish decide to do something, they do it the best they possibly can. Not just a can of spray paint; but taking lanes from traffic, closing some streets altogether to cars, introducing bike friendly crossings, having bike/pedestrian priority crossings at junctions etc etc. they recognise the compromises that inevitably stem from believing bike is best, and accept them. All too often in the UK, you get the sense that planners and engineers know they have to do something, but can't quite stomach the true consequences of that decision and we end up with the useless, underused and often dangerous rubbish that passes for cycling infrastructure here.

|

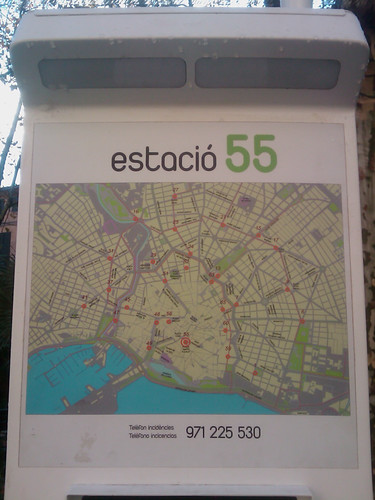

| Bike network map on docking station |

Beyond the evidence literally on the ground, there are also actually people on bikes. There are bikes parked on stands that once would have been all for mopeds. There are bike shops doing bike maintenance and selling stylish fixies. There is advertising using bikes as the backdrop. The next time I am there, I am sure that the balance of sensible upright bike v cheap knobbly tyred mountain bike with unsuitable suspension will have shifted in favour of the more elegant way to travel, and lo, a utility bike culture will have taken hold. Don't forget that sport cycling in Spain is a major deal, much more so I suspect than in the UK, so getting people to consider cycling for transport rather than just sport is perhaps a bigger stretch, although equally more people are used to cycling regularly. The point is that when I first came here 9 years ago, a bicycle would have been a rare beast in the city. Not now. There are painted bikes on the surfacing of segregated cycle paths, and real ones riding over - two facts not unrelated, I believe.

28 November 2011

The Green Grid

We have been doing some research into the way that Cardiff can be read as a city. Our thesis is that the park sof Cardiff are it's key characteristic, and can therefore be used as the structuring element that can organise the whole.

We propose that the main "anchoring" parks of Cardiff can become the attractors at the ends of green fingers that stretch out into the suburbs and beyond. Where an anchoring park is missing, then current landfill sites can be re-imagined as the new urban parks that perform the anchoring role that the great Victorian parks do elsewhere.

These green fingers are mostly already in-situ, and the axial (from outside to centre) connections are strong. Where the connectivity of this network fails is in the radial (radiating out from the centre) direction. The green grid needs to be augmented by creating links, joining pocket parks, greening previously derelict or brownfield land.

This green grid of connected parkland and found green space conveniently forms a new transport grid overlaid over the old and defunct road system, but luckily just for bikes and pedestrians. Here is our initial proposal which comes with a healthy debt of respect to Dr Beehooving at CycleSpace, of course, who is the pre-eminent expert in the field.

Presented at the Welsh School of Architecture, Post-Industrial Seminar, November 2011.

4 October 2011

Private Use of Public Space

There is always a lot of discussion in architectural circles about the "privatisation of public space". I shall illustrate what this frighteningly architectural phrase means, by referring to the example of shopping centres.

Once upon a time, a shopping centre was an easy concept to understand - a place where shops were collected together indoors, and they were equally easy to spot - they often helpfully had the name "shopping centre" stencilled on the outside.

|

| I think this is Edmonton Green Shopping Centre |

It was easy to see where they started and where they finished (doors to enter and leave) and it would therefore be reasonable to assume that they were indeed private space. Even if the mall formed an important connection or route within a city, it would be normal to assume it would close at 5.30pm, and reopen at 9.00am. You would not have been surprised to know it was owned by private enterprise, and not the public in the form of the Local Council.

But shopping centre design moves on. Even the name moves on - they are now malls, or arcades. In Cardiff, the people of the capital city are the proud recipients of St David's 2 (the sequel), which has the traditional spine route, covered, on two levels. There are doors to enter and leave and there is an anchor store at the end - John Lewis; thus propelling Cardiff into the big time. All very familiar thus far, but also all very obsolete. Because SD2, as we are encouraged to call it, might be the last hurrah of this now familiar typology. In Liverpool and Bristol, amongst others, new kinds of shopping centre have been developed and they look a lot like any old part of the town. In fact, they look a lot different to what we have become accustomed to believe a shopping centre should look like.

|

| Part of Cabot Circus, Bristol |

These new kid on the block have streets, townscape and urban scale. They are open to the elements. They might even have roads with traffic, but they certainly do not have doors to enter and leave. You would be forgiven for thinking that they are simply bits of the city that host them, although with less litter. However, they are not. They are private space. They are controlled by private enterprise, and if you start taking photos, polite well dressed gentlemen with radio earpieces and clip-on ties will appear and ask you to leave.

These bits of city are therefore certainly not bits of city in the traditional sense. So the urbanists and theorists get excited about sanitisation of space, the loss of the right to protest, rights of access, rights of assembly, the impact of private ownership within public space etc etc. But in truth, the ubanists have missed the boat. This privatisation of public space has been going on for years under our very noses with very little complaint. Large chunks of precious public realm have been enclosed and fenced off, with the process starting nearly 100 years ago. The space demarcated for motoring, a particularly private pursuit, has been expanding ever since.

The amount of land dedicated to the private motor car in urban centres, for both its movement and storage, is surely staggering. One only needs to consider the rents that could be achieved on the square footage occupied at present for free. The effect of this "enclosure" is quite debilitating to a sense of community and civility.

What is required is an about-turn in how we think about the use of space in cities. It is simple and obvious; the self propelled citizens should be in the role of the occupiers whereas the motor-powered citizens must be the guests. This is where the role of the bicycle is critical as a tool of radical thinking. You see, by making the effort to make cycling easy, for instance by providing quality segregated infrastructure, a city would thus overtly state its position that non-motorised citizens (pedestrians and cyclists) are welcomed by right, whereas the motorised are tolerated by necessity. By building segregated cycling infrastructure and all the necessary compromises to the hegemony of cars that go with that, a city will be reclaiming space for all its citizens, for Civitas.

9 August 2011

the Incredible Shrinking City

More thoughts, slow in gestation, from our recent trip to Copenhagen:

The steady pace of cycling in Copenhagen's cyle lanes, combined with the subjective safety they create in ones mind has the excellent effect of shrinking the city to a different scale. We happen to be well versed in the art of walking around cities and understand the scale and possibilities of distance and time as pedestrians. But this bike contraption thingy shrinks distance and opens up opportunities in an incredible way, when combined with the simple device of a safe, dedicated cycling infrastructure. Freedom from the mysteries of public transport, freedom from the motor car and the niceties of parking, directions, maps and getting lost. This exhilarating sense of freedom in all senses must have been what drove millions of people to take to the bicycle a century ago.

In urban planning, we often see masterplans prepared which attempt to consider the idea of "walkability" - whereby facilities and functions, or connections to other transport opportunities, are designed to be within certain walking times or distances. This is clearly a sensible and laudable way to proceed. But, I wonder what impact there might be on the flexibility and practicality of masterplans were an additional layer of "cyclability" to be added.

If the infrastructure was to be put in to a new development from the beginning, to allow this secondary layer of cyclability to operate beyond the normal walking radii, many possibilites might open up. Putting the car just a stage lower down the mental priority list might also help cut the short, local trips that get in the way of the journeys that the car is clearly very good at - long, fast trips from point to point over a regional scale. Not the quick trip to the shops or picking the kids up from school. And I hold no truck with the idea that just because it hasn't been done before, or done elsewhere that this would be a waste of time. Presumably, the City of Copenhagen started with just one cycle lane somewhere. Look what they managed in the meantime.

With the simple addition of "Cyclability" into the design mix, the Incredible Shrinking City would have neighbourhoods that were more civilised, more attractive and just that little bit more gentle of pace.

The steady pace of cycling in Copenhagen's cyle lanes, combined with the subjective safety they create in ones mind has the excellent effect of shrinking the city to a different scale. We happen to be well versed in the art of walking around cities and understand the scale and possibilities of distance and time as pedestrians. But this bike contraption thingy shrinks distance and opens up opportunities in an incredible way, when combined with the simple device of a safe, dedicated cycling infrastructure. Freedom from the mysteries of public transport, freedom from the motor car and the niceties of parking, directions, maps and getting lost. This exhilarating sense of freedom in all senses must have been what drove millions of people to take to the bicycle a century ago.

In urban planning, we often see masterplans prepared which attempt to consider the idea of "walkability" - whereby facilities and functions, or connections to other transport opportunities, are designed to be within certain walking times or distances. This is clearly a sensible and laudable way to proceed. But, I wonder what impact there might be on the flexibility and practicality of masterplans were an additional layer of "cyclability" to be added.

If the infrastructure was to be put in to a new development from the beginning, to allow this secondary layer of cyclability to operate beyond the normal walking radii, many possibilites might open up. Putting the car just a stage lower down the mental priority list might also help cut the short, local trips that get in the way of the journeys that the car is clearly very good at - long, fast trips from point to point over a regional scale. Not the quick trip to the shops or picking the kids up from school. And I hold no truck with the idea that just because it hasn't been done before, or done elsewhere that this would be a waste of time. Presumably, the City of Copenhagen started with just one cycle lane somewhere. Look what they managed in the meantime.

With the simple addition of "Cyclability" into the design mix, the Incredible Shrinking City would have neighbourhoods that were more civilised, more attractive and just that little bit more gentle of pace.

16 May 2011

The Bicing on the Cake. Viva Espana, Part 3

We were in the Catalan capital this week whilst Marga was invited to teach at the Barcelona School of Architecture. I continued to be impressed and amazed by the transformation of Barcelona Barcelona Barcelona

|

| So popular in fact that we've had to air-brush out all the cyclists just so you can see the view |

9 May 2011

Damn You, Johnny Foreigner. Viva Espana, Part 2

Here is a nice photo of No.1 son on the lookout for some exemplar cycling infrastructure and the signs of a maturing cycling culture. Even at his tender age, his continental blood makes him inherently more sensitive and understanding of urban design and the nuances of public/private space. That and having his parents blather on about it more or less constantly. Poor little thing.

But success! Even in the unprepossessing sea-side town of Sitges, near Barcelona Cardiff

Yes, damn you Johnny Foreigner with your suave easy urbanism and slow, silky football skills. There are rules about this sort of thing you know, and this is not the done thing. OK, so it's not the best (the trees and bollards are a slight inconvenience), but the shocking truth that you can choose which transport methods get priority in an urban area, rather than it being an unquestionable unchanging reality, is what I'm getting at here.

4 May 2011

Viva Espana, Part 1

We've been away in Spain, where we took a trip out of Barcelona - where Marga is currently teaching at the School of Architecture - to Sitges. This was a renowned centre of counterculture in the past, which continues into the present in the form of a Carnival and film festival. Proximity to Barcelona means it is a popular weekend day-trip for the citizens of Barcelona, and the admirable attitude to city planning that we all know from Barcelona is of course present in Sitges too - as it is all across Spain. I was struck by the simple example of the car park we parked in (there were 9 of us in the car, so an attempt to make an efficient journey was made). The car park has been excavated beneath an existing street, on several levels with simple access ramps, lifts and stairs arriving at pavement levels above - where the street has been re-instated over the parking bays.

I realise it may be heretical for a cyclist to wax lyrical about a car park, but I believe the approach in Sitges to this simple intervention belies a more mature and long-term approach to urban thinking than has ever been the case in the UK. It would be highly unlikley for a similarly sized seaside town in Britain to fund an underground carpark of this scale, preferring probably the above ground or multi-storey approach. And yet this solution in Sitges re-instated and significantly improved the public realm, left the scale of the area intact, hid cars away out of sight and ensured that the people were made to feel important, rather than overpowering them with a massive visible sign of car domination.

What a tragic lack of confidence we have in our own rights as citizens that we don't seem to demand the same quality of urban spaces and experiences that are common in Spain for instance. We deserve better, but we will never get it unless we believe we deserve it.

30 March 2011

A Coalition of the Willing

There are many obstacles to the goal of seeing separated infrastructure along the lines of the Dutch model here in UK

My proposal is that as well as building political will and social acceptance, building technical capacity is crucial. As might be imagined, highway engineering and design is a highly formalised and codified activity – this is not surprising. But what might be more surprising to some is the degree to which this comment also applies to urban design, architecture, masterplanning and landscape architecture – roles which might be traditionally regarded as somehow more artistic endeavours.

When embarking on a masterplan project, it is the connections which become one of the primary building blocks for the designers. Even at concept stage, with pencil in hand, designers need to be mindful of technical best practice and regulations, particularly when looking at public realm design, paths and roads. Vision splays, turning circles, fire appliance access – like them or loathe them, these are the ground rules of any scheme. There are a few key documents to refer to, notable amongst them the Manual for Streets and Manual for Streets Part 2 (particularly on residential or urban schemes).

I see an incredible opportunity in bringing the immense database of knowledge available on building cycling infrastructure in Holland – collected in large part on the Fietsberaad website – to a wider technical audience in the UK

The idea being that by influencing those who set the ground rules with pencil in hand, then you make it easier to make space for suitable and excellent infrastructure from day one.

I believe architects, urban designers and masterplanners will be open-minded to this kind of information, and they can in turn pressurise other design team professionals on design teams to push this agenda forward. At the same time, I can see the CEGB building alliances with the professional institutions such as the RIBA, RTPI and CIHT, who can in turn influence the preparation of technical guidance. For instance, the CIHT were authors of Manual for Streets Part 2 – this was not a “Government” publication handed down on tablets of stone, but rather a document prepared by a learned institute. It is that learned institute we need to influence and persuade as much as any politician or economist.

The Manual for Streets already pushes the boundaries of what many typical municipal highway engineers might have thought reasonable and acceptable just a few years ago. It is already allowing us to discuss in meaningful terms a rebalancing of the urban spatial environment in favour of pedestrians and non-motorised transport. By building a coalition of the willing and giving them the tools to deliver, who knows how much further we can go?

22 March 2011

A New Wonder Material for Paving

|

| View down from Capital Tower, onto Greyfriars Road |

Can you see the millions of tiny white dots all over the road and pavement? Chewing gum. When you think about the sheer number of times used gum must have been gobbed out to create this urban patchwork, it is quite disgusting.

However, of more interest to me are the surfacing possibilities here - I mean, just look at this stuff, it is completely impervious to weather, traffic, cleaning, it doesn't rot (does it?), it won't discolour, it has great grip and a pleasant minty taste. It looks like the age of tarmacadam is over.

18 March 2011

Crystal Ball Gazing

We are pleased to have come across this site CFhub.org.uk, which is a forum to bring together everyone in Cardiff who has an interest in environmental issues. This seems like an excellent example of network building, with a extremely sensible and useful summary of events going on in Cardiff. Hats off to the clearly enthusiastic and passionate work of the organisers.

From this new (to us) site, we were reminded about the Retrofit2050 research project run by our friend and colleague Prof. Malcolm Eames. We did some architectural type research related to this back in 2005 at Gaunt Francis Architects, when we produced an imagined image of what Cardiff might be like in 2055, related to the Council's celebrations for 50yrs as a Capital City. I'd like to think that we anticipated many of the issues that have since come to the forefront; retrofitting, hydrogen, water transportation, green infrastructure - although the cancelling of the Severn Barrage was not one we got right; perhaps it will come back another day?

We also stupidly missed the inevitable return of mass cycling, heralded by a new appreciation and knowledge of cycling infrastructure, the seeds of which have been sown at the Cycling Embassy of Great Britain with their growing wiki; http://www.cycling-embassy.org.uk/node/226

From this new (to us) site, we were reminded about the Retrofit2050 research project run by our friend and colleague Prof. Malcolm Eames. We did some architectural type research related to this back in 2005 at Gaunt Francis Architects, when we produced an imagined image of what Cardiff might be like in 2055, related to the Council's celebrations for 50yrs as a Capital City. I'd like to think that we anticipated many of the issues that have since come to the forefront; retrofitting, hydrogen, water transportation, green infrastructure - although the cancelling of the Severn Barrage was not one we got right; perhaps it will come back another day?

We also stupidly missed the inevitable return of mass cycling, heralded by a new appreciation and knowledge of cycling infrastructure, the seeds of which have been sown at the Cycling Embassy of Great Britain with their growing wiki; http://www.cycling-embassy.org.uk/node/226

3 March 2011

Monorail planned for Cardiff

Monorail planned for Cardiff - Business News - Business - WalesOnline

Came across this story about a monorail planned for the city centre, linking Cardiff Bay with Cardiff Central station. Classic pie-in-the-sky stuff, but whenever this kind of story rears its head, I can't help but think of...

Marge v The Monorail.

One technician suggests cutting the power, but alas, the monorail

is solar-powered. (``Solar power. When will people learn?'')

But miracle of miracles, Springfield suffers a solar eclipse!

The train grinds to a halt, and all celebrate. The eclipse

ends, and the train speeds off again.

There truly is a Simpsons episode for every occasion.

Came across this story about a monorail planned for the city centre, linking Cardiff Bay with Cardiff Central station. Classic pie-in-the-sky stuff, but whenever this kind of story rears its head, I can't help but think of...

Marge v The Monorail.

One technician suggests cutting the power, but alas, the monorail

is solar-powered. (``Solar power. When will people learn?'')

But miracle of miracles, Springfield suffers a solar eclipse!

The train grinds to a halt, and all celebrate. The eclipse

ends, and the train speeds off again.

There truly is a Simpsons episode for every occasion.

15 February 2011

A Civil Society Needs the Bicycle

In an earlier post, I referred to the work of Jan Gehl and his approach to “liveable cities”. One of the things he is trying to do is to civilise our cities, and remind us that the human scale is important. It is why some of his most renowned work has revolved around re-discovering pedestrian routes and re-thinking the balance between cars and people.

If a city with a considered balance between streets and roads, between people and cars can be considered civilised, then another measure of civility is surely how a city treats its cyclists.

So, if you believe that in order to encourage cycling, there needs to be an attention to cycling infrastructure on the Dutch or Danish model, then the way a city treats its cyclists has a physical form. There is a visible demonstration of commitment. This is an important distinction to make, as it means you can’t hide from the political implications of wanting to create a “world class” city (an avowed mission of the good burghers of Cardiff, unlikely as it may seem) – an aspiration of that kind has a real effect on the ground – your progress towards that goal can be measured in blue paint and kerbs.

A civilised attitude to accommodating cyclists and thus offering citizens a safe and viable alternative mode of transport also brings its own rewards, in the shape of benefits which themselves have an impact on quality of life and “liveability”. Improved health, less pollution, less congestion, more efficient public transport are just some of the widely understood arguments, which seem to be happily accepted by Councils and Governments everywhere in terms of written policies. What they haven’t realised is that accepting the argument and spouting platitudes is easy. It is the wholesale re-allocation of street space that is hard – and the lack of action stares us in the face.

But how about some of the less obvious, but equally – if not more – important benefits that we should also champion. How about seeing people with a smile on their face as they cycle along? How about just being able to see people’s faces? How about a gentler pace in peace and quiet in the morning rush hour with just the tinkle of bells and whirring of gears to accompany the birdsong? How about the opportunity to say good morning to a fellow coommuter?

All intangible in terms of benefit. All immeasurable and unquantifiable. And yet at the very heart of what it is to be civilised.

9 February 2011

Where Were All The Cars?

|

| Cardiff Queen Street, http://www.oldukphotos.com/ |

I continue to read “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City

I am always intrigued by looking at old photographs of familiar places, particular city centres. I am constantly struck by how “modern” life seems in the social sense. There is density, vibrancy and endless activity. In fact, there are people everywhere – on the street, on the pavement. I now wonder if this was all possible because in those days, the “street” was a genuine multi-user experience, but crucially the balance of power was with the slowest – pedestrians, cyclists, horse and cart. The new trams and trolleybuses just had to mix it up with everyone else as best they could. We may well blurt out “look! there are no cars!” Of course, they weren’t really popular or present in any great numbers until the 1920’s in the USA and possibly a little later in the UK

This makes a stark contrast with photos taken from similar locations today. The most noticeable change is that the street has been almost completely devoted to a single mode of transport – the car. It is now clearly a road. Other, slower, occupants of the city centre have to fight it out on the margins, literally. Indeed, encroaching on the right of passage of the car has been classified in our minds (if not necessarily in our laws) as some kind of offence – “jaywalking” as the Americans call it.

The fact that the motor-car gained this pre-eminence in our mental and physical urban space created the “bull in society’s china shop” as described by Mikael Colville-Andersen on Copenhagenize, and is the key to understanding why we need the bicycle in the struggle to help turn the road back into a street. It is the bicycle that can now challenge the widely held assumption that cars have the right to the road. It is by challenging this so-called right that we can win back the civic space that was the street of old. It is by challenging this hegemony that we can create the space for the decent, well designed cycling infrastructure in cities that could unlock the pent-up demand for alternative ways of travelling.

30 January 2011

The Power of Ideas

As I was cycling home in the pouring rain the other day, it struck me that the car is as dangerous an idea as it is a physical object. The reasons that people consider the car to be so successful are the very same reasons why the car is so problematic; they are isolating, they promote a (false) sense of security, they have the appearance of convenience and they are desirable. Or at least that is what people believe.

Why do people believe these things? In large part, I presume that an endless, expensive and all-pervading campaign of marketing and advertising has done its job. I also presume that like most new technologies, the motor car had to survive the early knocks and the battle to “define” what this new technology was (when they first arrived on the street, they were considered “death machines”, driven by “road hogs” and “speed maniacs”).

The question is probably not even relevant for recent generations, who have not had to make the paradigm shift that allowed the car into our lives – it was already there. So how did it do it in the first place? And, the question that really intrigues me - What subtle shifts in society and thinking allowed us to hand over huge swathes of public space to an essentially private pursuit?

From an urban planning point of view, the founding in 1929 of a small town called Radburn located within Fair Lawn , New Jersey

At Radburn, here was the urban manifestation of this process for all to see – and just as importantly for others to be influenced by. The spaces that were previously the “streets” for all and sundry to use by collaboration and compromise became the “roads” for motor cars only. Pedestrians and cyclists were given their own alternative spaces and routes. Great, you may cry – exactly the model of segregation we want! The problem is that by handing over this road space to cars, particularly in urban situations, and allowing the transportation system to become dictated by the needs of one particular mode, we have also given away our civic space. The road is for cars and that is that.

In order to now re-engineer that same road space to create the segregation and cycling infrastructure we so desire, we have to overcome the idea that the space somehow “belongs” to the motor car. Possession is, as the old saying goes, nine-tenths of the law. The trick that was pulled off by “motordom” in the 20’s is the same trick needed now and it is going to be a very hard sell. But, it happened before and it has happened again, not only in the famous cycling nations of Holland and Denmark , but seemingly unlikely places such as Paris and Barcelona

20 January 2011

The Wisdom of Jan Gehl

"We don't need great architectural monuments to make a city a nice place to live, just make the public spaces nicer "

A much better conclusion than the one I wrote to the piece below, courtesy of Jan Gehl speaking at "Making Tomorrow's Liveable Cities: Urban Planning in a Cold Climate" yesterday.

http://www.economistconferences.co.uk/event/creating-tomorrows-liveable-cities/3832

A much better conclusion than the one I wrote to the piece below, courtesy of Jan Gehl speaking at "Making Tomorrow's Liveable Cities: Urban Planning in a Cold Climate" yesterday.

http://www.economistconferences.co.uk/event/creating-tomorrows-liveable-cities/3832

18 January 2011

Opportunity Lost in High Street, Cardiff

|

High Street, Cardiff |

The upgrade of the Hayes from the new Central Library to Queen Street is a bold, minimal and stylish intervention and deserves praise for the quality of materials, workmanship and layout. It seems that the design aspirations have been matched by the outcome and that rare combination should be recognised with appropriate praise.

The danger of course was that other parts of Cardiff

Of course, these improvements were always going to leave Queen Street as a visual problem – the busy floor layout and excessive clutter now looks very clumsy and provincial compared with the Hayes – but this work was carried out relatively recently, so I suppose we are stuck with it and its surface that becomes unexpectedly slippery in the gentle drizzle that occasionally falls here.

So, the unfortunate legacy of Queen Street aside, the bar has been raised and the patient citizens of Cardiff

There are clearly many technical and economic constraints - this was obviously not going to be a straightforward pedestrianisation exercise. So why then go for the trendy idea of shared surface, only to have to compromise under the inevitable (and genuine) criticism of the local disabled user group? The white line delineating a central carriageway is horrible and spoils what is otherwise a very reasonable and high quality choice of materials. But the real icing on the cake is all the “stuff” above ground. For instance, one wonders how much of St Mary Street could have been similarly improved, if the money spent on several hundred cast iron bollards now gracing the view (and without discernable purpose) had been saved.

Our eyes have become so accustomed to this sort of visual mess in our urban spaces that it actually takes an effort of will to see it. What level of processing power must our brains have to devote to filtering out this chaos? Our brains constantly undertake real-time special effects wizadry worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster. But once you’ve seen it, the trick is lost and you suddenly can’t ignore it - it becomes all the more real; bollards, lampposts (just horrible) signs etc…indeed you can barely see the Castle through it all.

Did the designers not see the restraint in the design of the Hayes? Were they deaf to the voice of Mies imploring “less is more”? The council want to persuade us that Cardiff aspires to be a European Capital City

11 January 2011

Bankside Bike Shed

My good friend and amateur frame designer Mark, who has some information on his handiwork at

http://www.welwynmachineworks.blogspot.com/ has pointed me in the direction of a new architectural competition organised by the Architecture Foundation.It is for an innovative and portable modular bike storage facility, which also needs to act as a signpost or branding opportunity.

The details/brief are at http://www.architecturefoundation.org.uk/assets/files/Competitions/Bankside%20BikeShed/Bankside%20BikeShed%20Brief.pdf and we are tempted to give it a whirl.

If there are any ideas on what the ideal bike storage should include, feel free to let us know. We are thinking this is an ideal way of introducing some ideas from Holland and Denmark, where this sort of thing is not exactly thought of as cutting edge, to the UK - where it is.

10 October 2010

Urban Design for Students without a Design Background

Marga recently attended the iBEE Conference in Sheffield, and presented an interactive workshop about how to teach urban design to students without a design background.

These methods may also have wider applicability, especially with community engagement. Toby will be studying this in more detail later in the month, when he attends a course run by Community Planning (http://www.communityplanning.net/) in London: Course Details

Marga's paper can be viewed by following this link: iBEE Conference Workshop.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)